There's something amiss in the land below the sea...

On November 22nd, the Netherlands is going to the polls. This article provides a unique perspective of the country in the runup to the election.

This year on the 22nd of November, the Netherlands is yet again headed for an election, and for the first time since 2010, Mark Rutte won’t be on the ballet. We’re being bombarded by graphics, talkshows, and news articles covering the election, and I wanted to start this substack off with a bit of context in the runup to the election. The country is in a strange state and hopefully this article provides a bit of a unique perspective on what precisely is going on.

Often, I’m baffled when reading headlines of the peculiar, oxymoronic, country built from the sea that the Netherlands is, and I suppose this is my attempt at understanding it a bit better and forming my own view in the coming election. I have many bewildering feelings about the country and this article serves as my attempt to set down some thoughts and observations.

Since this article is a bit of an exercise and an experiment I’d love feedback, so feel free to let me know what you think. I’d also love to get as many people as possible reading the article, so please share it with anyone that you think might be interested. I’m also curious to see if this substack thing might lead somewhere - so feel free to subscribe. I promise to send around something interesting at least once (likely more often) a month.

So let’s begin with a bit of a look back at the Rutte years, shall we?

Mark Rutte’s many scandals

Mark Rutte has been the prime minister of the Netherlands for 13 scandal ridden years. Throughout these years, Rutte has proven remarkably capable at evading responsibility and letting scandals slip.

The list of Rutte’s crises is extensive and at times it’s easy to forget just how many took place under his leadership. Among the more notorious is the toeslagen (childcare subsidy) affair where around 26,000 parents, largely coming from migrant communities (impacting 70,000 children), were falsely accused of committing welfare subsidy fraud.

As a consequence, the parents were told to pay back immense amounts of money back to the Dutch state, frequently resulting in financial devastation and emotional anguish. Families went bankrupt, many parents lost custody of their kids, and one parent committed suicide, allegedly because of the persistent chasing of the tax authorities. Even more damming, it became clear that compensation for the parents might not be finished until 2030.As of writing, the most impacted families are still waiting for compensation and its implementation has been a mess.

Other crises include the botched evacuation of Afghanistan (and especially of Afghans who helped the Dutch state and as consequence, were under threat once the Taliban assumed power), the ministry of foreign affairs admitting and apologizing for an internal culture of institutional racism, and a scandal where it was found that Rutte deleted his work phone messages on a daily basis, effectively evading transparency.

Rutte’s modus operandi throughout his premiership ultimately became called the “Rutte Doctrine” where civil servants were notably hesitant to talk to the press or other political leaders, further evading transparency and inducing a general culture of political opacity. At the center of these scandals is a Dutch state that has been unwilling to acknowledge responsibility, evinces a clear distrust of its own population, and unable to maintain standards of transparency and accountability.

This too, is the Netherlands.

And yet, here we are in 2023. With the fourth and final Rutte cabinet falling (apparently) over refugee reunification family policies, 2023 will end with the Netherlands voting for a new prime minister. Despite these scandals, Rutte’s VVD is still leading the polls at the moment and this time, the leadership tells us that it’s really changed. Surely…

The election also features some new faces, including the rise of a new party, the “New Social Contract” with Pieter Omtzigt, we have the farmer’s party BBB, and a newly unified left-green coalition party. The ever-notorious and islamophobia Geert Wilders from PVV is also rising in the polls.

Whoever the new prime minister is going to be will have some significant work ahead of themselves to mend the country from their predecessor. Let’s now explore some of the more prominent issues for voters ahead of the election.

Onwards to the polls

For the nearly 18 million people living in the Netherlands, the most important topics in the election are, according to an Ipsos poll, inflation and the cost of living, the healthcare system, immigration and asylum, the housing market, and the climate emergency and sustainability (essentially in that order).

These priorities differ between the older and the younger populations. Whereas the young are primarily concerned with the housing market, the cost of living, and the climate / sustainability, the older population is mostly concerned with healthcare and immigration.

Of course this speaks to particular concerns that align with the different class positions of the two age groups - whereas many of the older generation have benefitted from skyrocketing housing valuation over the past decades, the young have seen their chances at home ownership dwindle. Since 35% of the overall population believe the upcoming election should focus on the cost of living and inflation, it is here to which we now turn.

Inequality, poverty, housing, and inflation.

Generally speaking, poverty and income inequality is fairly low in the Netherlands, although it is unequally spread across the country and we can debate about how poverty is calculated by the national bureau of stats in the first place. Nevertheless, according to the central bureau of statistics, only around 4.8% of the population live in poverty. The bureau of statistics is also warning that unless dramatic changes are made, overall poverty is likely increase by around 1% in 2024, leading to nearly a million Dutch residents below the poverty line.

But looking a bit closer at the data reveals a starker picture of poverty in the Netherlands. A doctrine of labour flexibilisation has reined supreme in the Netherlands the past decades and these policies have had a significant influence on the risk of poverty for the Dutch working population. The “working, yet poor” project is a recommendation when it comes to understanding that the phenomenon of the working poor in the Netherlands (those with employment and yet still struggling to meet basic needs). As Dutch labour policies have emphasized flexibility and precarity rather than protection and certainty, the share of the working yet poor population has risen.

The Netherlands is unique in that it has the lowest share of workers employed through standard open-ended full-time employment contracts, currently at around 35% and falling. No other EU country has a share under 50%. Workers with flexible and temporary contracts are at a particularly high risk of vulnerability as they have far fewer employment protections, especially if work becomes scarce and contracts end.

While the political discourse has continued to be one of encouraging “flexibilization” and a dynamic employment system for some parties, others are beginning to emphasize the important of standard full-time open-ended contracts.

This situation is slowly changing, largely through the efforts of labour unions and collective action. For example, the FNV (the largest Dutch labour union) has put in place measures to protect self-employed workers within collective labour agreements, such as a requirement for their pay to be at least 150% that of employed workers in the architecture sector. This sounds lucrative, but remember that self-employed workers have far fewer protections and access to social provisioning than their employed counterparts.

The hidden reality of migrant workers in the Netherlands

Too often are migrant workers forgotten in discussions on poverty and inequality in the Netherlands. In reality, many thousands of migrants are living in unsuitable conditions, paid well-below the salary of comparable Dutch nationals, and face further abuse and stereotyping when participating in social life.

There are currently an estimated 800,000 migrant workers in the Netherlands, the majority of whom are employed in the agricultural and construction sectors. Most of these workers come from Eastern European countries, predominantly from Poland and Romania.

The largest labour union in the Netherlands, FNV, has documented considerable abuse of these workers, ranging from underpayment, false promises upon arrival, insufficient provisioning of housing, and underrepresentation and protection by regulators and unions.

Martijn Balster, alderman of public housing in the Hague, described a common sight: “A Bulgarian family of 5, living in a room of 12 square meters with the walls black with mold, paying 1100 euros a month in rent. These are frequently the living circumstances observed by inspectors of the municipality of the Hague”.

Ironic for a self-proclaimed country of human rights and dignity.

The country is woefully unprepared to establish infrastructure for its dire need for migrant workers. Zembla, a Dutch investigative news show, conducted an investigation on the living circumstances of migrant workers and found that of the 25,000 living in the municipality of Roosendaal, only a few hundred had decent living conditions.

And yet, in full recognition of the mistreatment of migrant labourers, the political discussion has turned sour when it comes to them. Frequently there are reports wherein municipalities fight tooth and nail against the creation of housing complexes for migrant labourers, preferring instead to defer the problem elsewhere.

Additionally, although in political discussions party leaders have made fleeting reference to protecting migrant workers, few have explicitly stated plans to accomplish this and would rather repeat right-winged calls for stricter migration policies, avoiding the more contentious need to provide decent housing and suitable working conditions these workers.

Clearly this is unsustainable, but an urgent political question needs explicit asking: are we willing to continue the abuse of migrant workers for cheap construction and agricultural products? I sincerely hope the answer is a resounding no, but the lack of recognition this problem has received in the political debate fails to reassure.

For a short documentary piece on this (in Dutch - subtitles available) see:

And what about housing?

The costs of housing contribute massively to the prosperity (and lack thereof) of households in the Netherlands. Families with main earners under 35 spent on average 41% of their income on housing in 2021 - rising to 45% for those renting homes. Poorer households also spend increasingly spend a greater share on housing costs the poorer they are.

However, for the population of the Netherlands that owns homes, housing represents an altogether different economic significance. The difference in median wealth for households who own their homes versus those who rent is astronomical, and that’s even the case when we subtract the value of their homes from their overall wealth.

This isn’t a minor difference - it’s this exceptionally large difference in capital that results in multigenerational wealth transfers and the means to accrue further wealth. Often it is wealth, and not income, that offers opportunities such as access to cheaper mortgages, loans for starting businesses, among other advantages. Returns on wealth and capital have also increased over time relative to income - meaning that those who own are increasingly more prosperous compared to those who do not.

Not only is private wealth unevenly split across Dutch households, it is also increasingly large in comparison to public wealth. Since Rutte has been the prime minister, the ratio of net public wealth (the stocks, assets, public infrastructure, etc. owned by the state and other public entities) to total wealth has crashed. At the same time, private wealth has ballooned, meaning that private coffers are being filled while the state has less capital at its disposal.

This fall of public capital during Rutte’s premiership has impacts on social goods such as health and transport. In the next section, we’ll see how the privatization and marketization of public goods in the Netherlands has brought about problems the public health and transportation systems.

When listening to the party leaders discuss their proposals for the future of the country, I implore the reader to pay attention to wealth inequality. The plans diverge considerably, with the left calling for increasing tax on capital, and lowering the tax on labour. In contrast, VVD’s right has ripped a page from the 1980’s and called for austerity yet again…

Health and transport in the Netherlands - rising costs and struggling institutions.

Health in the Netherlands - rough for patients and doctors alike.

The Dutch healthcare system has been under pressure for decades and this doesn’t seem to be letting up. Expats living in the Netherlands coming from countries with robust healthcare systems are often shocked by some aspects that we seem to assume are normal in the Dutch healthcare system.

For example, being turned away for medical complaints and told to “try a paracetamol and come back later” is so normal in the Netherlands, expats often swap strategies on how to actually get medical attention from their doctors.

While this might attributable to a general callousness or a result of the peculiarities of Dutch medical training, I would argue that this is a consequence of a systemic and institutional crisis of a semi-privatized healthcare system that puts patient well-being second to cost prevention.

Back in 2021 during the height of the pandemic, I interviewed Dr. Ouafae Amekran, the owner of a clinic in the Hague. She made it clear to me that doctors in the Netherlands are under immense pressure to treat patients as quickly as possible. The pressure is institutional and financial - you’re compensated on a per-patient basis and encouraged to prevent patients from needing appointments with specialists. The time slots are either 10 or 20 minutes and patients know well how difficult it can be to get a forward to a specialist from their GPs. Dr. Amekran fights against this, arguing for the need to treat the patients with context and care, rather than as a set of appointments in a calendar.

And even despite this rapid, factory like pace that doctors are meant to churn through patients, healthcare costs are still rising. The Netherlands is spending the 10th greatest share of its GDP on healthcare in Europe, significantly higher than countries like Spain or the UK that have robust public healthcare systems and treat health as a right, not a luxury.

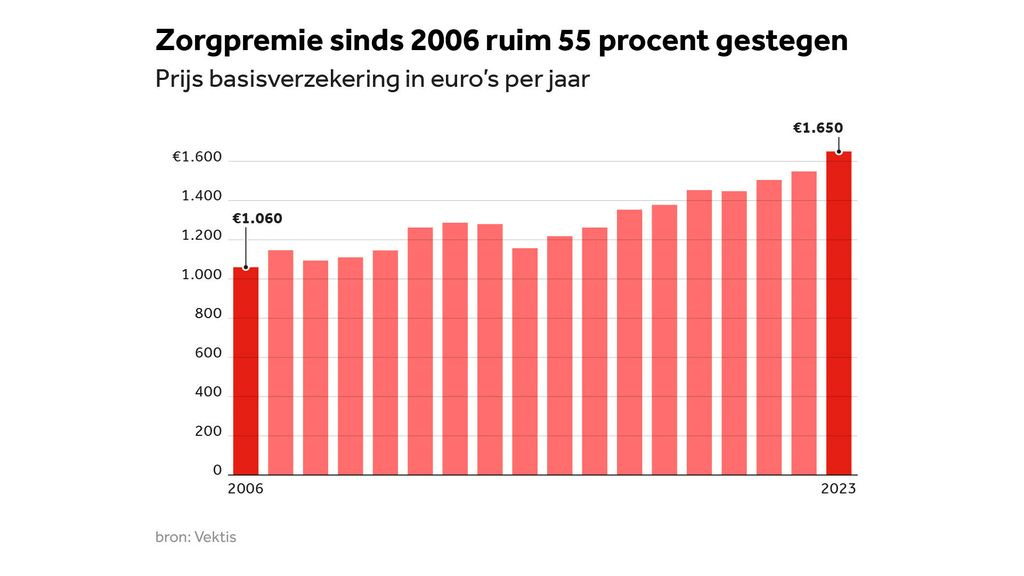

Patients too feel the institutional and financial pressure from the healthcare system. In 2024, the monthly health insurance premium in the Netherlands is going to rise by its greatest amount ever in a single year.

It’s important to remember that the healthcare system in the Netherlands was only privatized in 2006 and that we are surrounded by alternatives that work. The current system is failing at each of its goals: healthcare costs have risen, doctors are under immense pressure, patient care is lacking, and the economically precarious are avoiding the doctor as much as possible to avoid paying their eigen-risico costs. According to a survey, nearly 28% of survey participants avoid medical care because of the costs. For low-income residents, that skyrockets to nearly 40%.

In other words, the system is neither affordable, nor effective.

Oh the NS.

Since the pandemic, the NS has less trains on the tracks, perpetual staffing problems, and rising debts.

The NS is burning through money, and fast. In 2022, the NS had an annual loss of €304 million. €5,4 million was just from the NS paying customers back if their trains were too delayed.

To survive, it seems the leadership of the NS is relying on substantial state subsidies, dramatic price hikes, and fewer employees. These subsidies were put in place to keep the company afloat during the pandemic, but how is it that the train company still isn’t sustainable, even despite firing thousands of employees?

It doesn’t seem to be a decrease in ridership: the NS recorded 13.3 billion passengers in 2022, up 49% from 2021. Maybe it’s the unnecessary costs that the NS seems to be investing in? Consider the new “Intercity-new-generation” trains that the NS purchased, which appear to be breaking down and leading to an increase in delays. Having sat on these trains, if I’m being honest, I don’t really notice all that much of a difference from the previous models - why did we invest millions in them again?

Personnel costs? Nope, not that either. While these did rise between 2021 and 2022 by around 6.5%, revenue increased by over 49%. In fact, while many employees of the national train company are struggling to get by, especially during the cost of living crisis, the director was making a hefty half a million euros per year. Maybe that’s one salary that might be deserving of a cut.

Initially, it was expected that we would once again bear witness to another year of ticket price increases. The director of NS even flirted with the idea of introducing a “peak hour fee” for some connections during the peak hours, but this was rejected in parliament.

But here we have an example of a bit of a change of direction. On the 7th of November, 2023, it was announced that the NS wouldn’t increase domestic train tickets in 2024. International tickets and the OV-bikes would see price hikes, but the subscriptions and costs of individual domestic tickets would be frozen. A parliamentary majority decided that the ministry of infrastructure and the fund for mobility would sponsor the NS €120 million to cover the cost.

But let’s put this in an international perspective for a moment - what exactly are we doing here with our public transportation system? Is a price freeze really ambitious enough, and were we really considering discouraging train travel during peak hours?

In a time when the need for a robust and sustainable transportation system is so clearly urgent, how can the director of a majority state owned rail company even think to discourage train travel during peak hours by making it more expensive rather than increasing train volume and frequency to make it more appealing? Can’t we have ambition such as the city of Barcelona which cut public transport prices in half to help citizens during the cost of living crisis, rather than charge them more and call for staffing cuts? Or alternatively like Luxembourg and Malta, offering free public transport to treat mobility as a right, rather than a luxury.

How to pay for this? Well, perhaps a bit of extra revenue from the wealthiest 1% of the Netherlands, who are paying the smallest share of their income in taxes. It was estimated that making all public transportation in the Netherlands free would amount to around €4 billion. This is of course neglecting to take into account the advantages that it would have on health, the climate, and economic mobility.

Let’s think with a bit more clarity and aspiration when it comes to our public transport system.

Energy, climate, and sustainability.

If you’ve made it this far, I congratulate and thank you. We’re nearly there to the end, and there’s just so much more to say.

Of course with the war in Ukraine, the Netherlands like many other countries truly suffered as many struggled to warm their homes. The prices of energy in the Netherlands shot up rapidly - a consequence of the country’s dependency on natural gas and highly liberalized energy market.

But how could such a wealthy, progressive country still be so dependent on natural gas in the first place? Of course, a partial explanation are the immense reserves in Groningen, pumped from the earth to the detriment of local residents whose houses are collapsing. It might also be the impressive lobbying power of fossil fuel companies in the Netherlands - a report found that Dutch companies are still receiving tens of billions of euros for using fossil fuels each year. What does this dependency give us? Well, despite huge reserves and cozy relationships between politicians and oil and gas companies, the highest natural gas price in the world, apparently. Let’s not forget that energy companies made record-breaking profits while we sat in the cold.

To help cope with these energy prices, the Netherlands did implement a price cap on natural gas and electricity, but remember that this simply means that energy companies are being reimbursed for their costs above the cap through further energy subsidies. Let alone that this cap is still well-above the price from years ago.

There’s a lot to say about the energy makeup of the Netherlands, but I’ll let a few statistics do most of the talking.

Less than 16% of Dutch energy came from renewables last year. If we exclude biomass, which isn’t really all that green, it drops to under 9%. Solar and wind? 3.3% and 4.2% respectively.

And that’s the best year on record.

I wrote about the snails-pace energy transition taking place in Europe for Dutchnews and TNI. It became clear that to prevent this immoral energy pricing and heavily polluting energy system, we need a publicly owned and democratically run energy system.

Then we come to the environment.

Not a single body of water in the Netherlands meets the standards set by the EU. Let that statistic sink in for a moment.

The past years have been a cavalcade of environmental clashes in the country, from the stikstof crisis to Tata, Dow chemical, and Shell pumping the country’s water with toxic substances, to my own province’s shores being so oversaturated with PFAS that perhaps we shouldn’t even eat our mussels - a cultural heritage of the province. I’m a bit out of space for this piece, but I’m certain I’ll be writing more about the environmental situation in the future.

To resolve some of these environmental concerns, the previous cabinet attempted some rather indelicate proposals, such as broad requirements for the creation of new protected areas and additional requirements for farmers. The indelicate implementation of these policies ultimately led to a revolt by farmers and their supporters with tractors parker in the center of the Hague. Evidently, farming and the environment is a tricky subject in the country - one that I fear we still don’t recognize how far apart the society still stand divided on.

Nevertheless, political platforms are, at least explicitly, calling for a need to combine the needs of nature and agriculture and formulate a new plan for this. An ambitious idea, no doubt, but one urgently needed for the sake of the country. Perhaps rather than punish and shame the farming community of the country, we instead provide them with the means to protect the environment - not rhetorically, but financially and materially.

The election of November 22nd

As I’m writing, four parties are leading the polls in the upcoming parliamentary election:

VVD - Mark Rutte’s centre-right (leaning ever-righter), liberals, now headed by Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius.

NSC - new social contract a new party headed by Pieter Omtzigt.

PVDA/GL - the labour green coalition with Frans Timmermans as the candidate.

The far-right Islamophobic PVV with Geert Wilders making a resurgence.

While the election nears, it’s important to think actively about the visions these parties have for the country in relation to the problems I’ve described above. I understand the indulgence and desire of political apathy and nihilism - but we simply cannot afford this anymore.

It’s imperative to have an accurate understanding of each of the parties’ election programs which can be found here. Further information can also be found in the central planning bureau’s calculation of the costs and consequences of each election program, which can be found here. (Some parties have disagreed with the legitimacy of this calculation, and so aren’t included). It’s indeed a bureaucratic exercise with a faux sense of neutrality, but it’s important to look at nonetheless with a critical eye.

There is so much that I have yet to cover and couldn’t get to in this article and it swiftly became much longer than I had expected. Of course in the future I’ll cover more topics about the political situation of the Netherlands and anything else curious, political, and urgent. Feel free to subscribe to check out future writings!

For now, I implore those with the privileges to vote to do so. An election is an opportunity, one that we cannot let slip by.